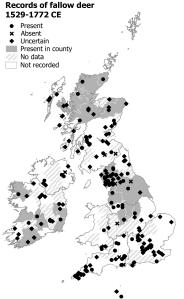

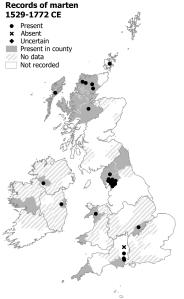

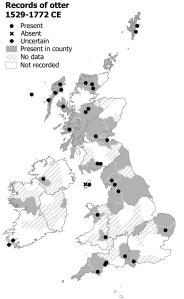

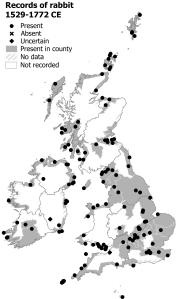

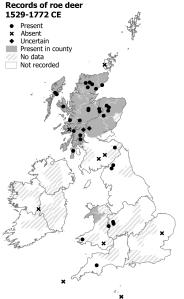

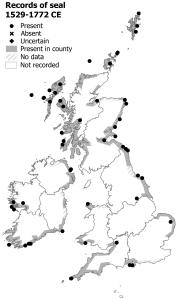

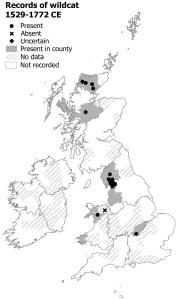

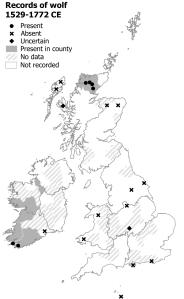

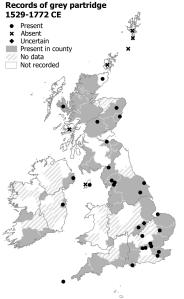

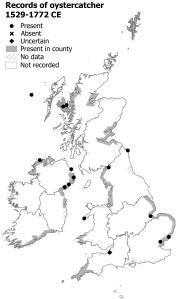

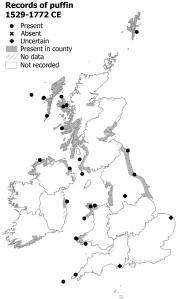

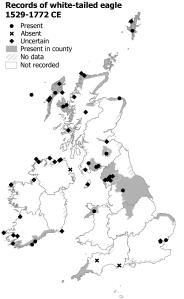

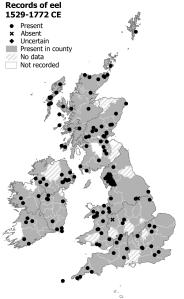

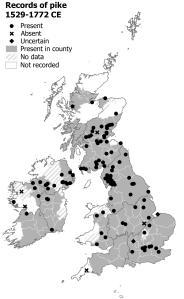

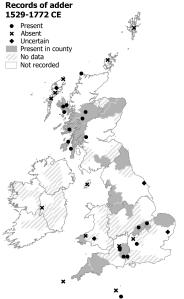

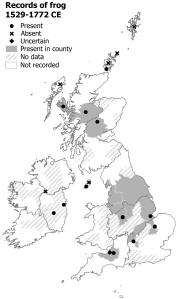

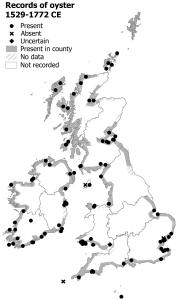

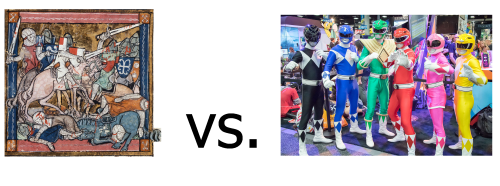

The following maps show the distribution of wildlife in Britain and Ireland around 250-500 years ago. They come from The Atlas of Early Modern Wildlife (order a copy here). They are under copyright and should not be copied or reposted without permission. If you refer to them in your work please cite me (Raye, 2023). A new map will be added to this list each month, so please follow me on Twitter or Mastodon to get updates.

N.B. These maps are slightly different to the ones published in the Atlas – the ones in the Atlas do not have keys, but instead have an inset of the modern distribution of species. I have also added to a few of these maps to reflect additional records. For ordinary use, the differences wont matter much.

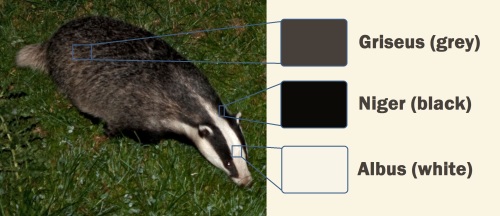

Mammals

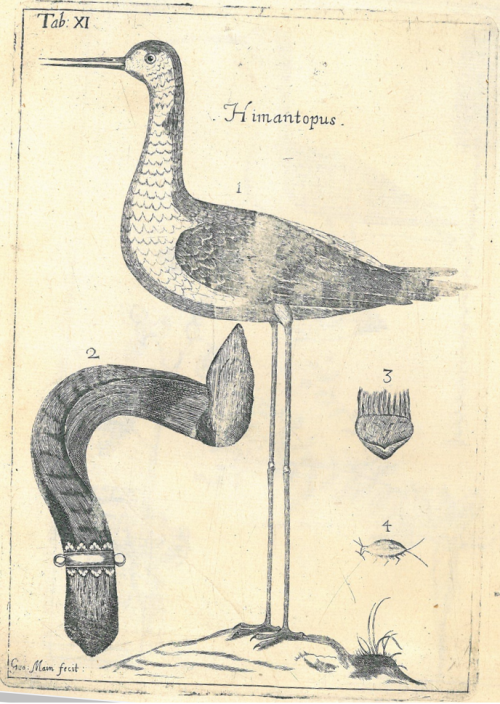

Birds

Fishes

Amphibians and Reptiles

Invertebrates

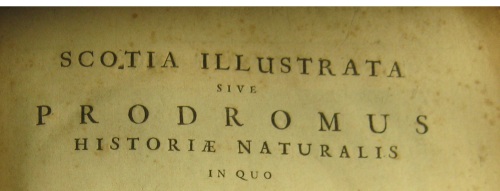

The database behind these maps includes over 10,000 early records of wildlife, drawn from over 200 natural history texts dating between 1519 and 1772 CE. The database itself will be shared in July 2023 with the release of the Atlas and a link will be added here.

The full version of the Atlas of Early Modern Wildlife has now been published by Pelagic Publishing (2023). It includes maps of over 150 species, as well as in-depth commentary on the identification, conservation status and historical distribution of each species. Please cite me if you refer to these maps (Raye, 2023). You can order a copy from Pelagic Publishing’s website, or wherever else you get books.

References

Raye, L. (2023) The Atlas of Early Modern Wildlife, London: Pelagic Publishing.