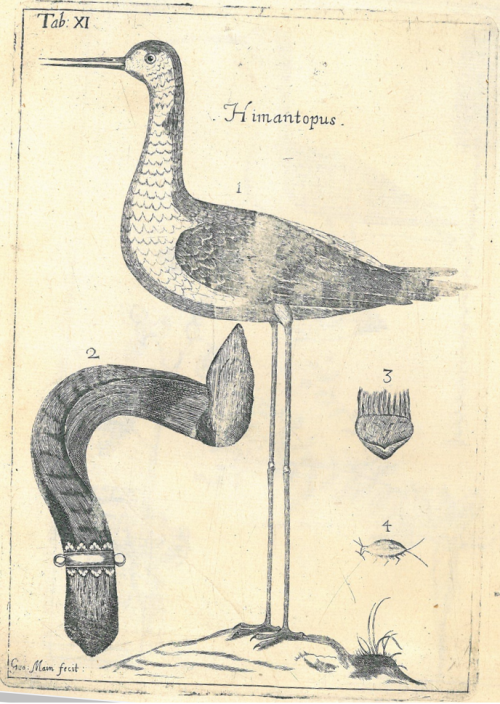

In my last blog post I announced I had found funding to start a research project looking at a seventeenth century Latin Natural History text. I am now well underway, kindly sponsored by the Antiquaries of London and the Alice McCosh Trust.

Robert Sibbald’s (1684) Scotia Illustrata is a really important text. One of the reasons for this is that it gives a full catalogue of wildlife found in seventeenth century Scotland. Most naturalists of the time period wanted to just write down every species of wildlife known at the time. Sibbald however, restricted himself to just writing about the species he had observed or had had people write to him about. That makes it a really important work for trying to reconstruct Scotland’s pre-industrial fauna. That includes some quite surprising species, and I’m planning to publish my findings next year.

Click more to keep reading.